Significant political processes never have a single cause. The ongoing revolution in Belarus also results from multiple factors; it is complicated and constantly changing. It is taking place in a country located at the meeting point of the West and the postimperial sphere of influence of Russia. Therefore, it contributes to the preservation or the collapse of a Russian neo-imperial agenda. For this reason, its outcome is crucial for the security of Russia’s European neighbors, and, as such, it engages the interests of the members of the European Union and NATO, including the US – the transatlantic alliance’s hegemon.

Author: Przemysław Żurawski vel Grajewski

Reasons – the legacy of history

Since the 13th century, Belarus was a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Since 1385, the two countries, as well as Poland, shared the same rulers. In 1569, it became part of the Duchy and thus formed, together with the Kingdom of Poland, the Commonwealth of Both Nations. Belarus has long democratic and parliamentary traditions – dating back to 1445.

The Moscow invasion of 1654–1667 resulted in a demographic ruin of the country (with the population loss reaching from 13% to 80%, depending on the region) and the disappearance of its elites. As a result, in the second half of the 17th century, Belarus became Polonized to a great extent – especially with respect to high culture[1]. At the end of the 18th century, Belarus was conquered by Russia and profoundly Russified in the following centuries. This process was combined with the destruction of the national achievements of previous eras – first by the tsarist rule, later by the communist USSR, and the periods of genocide, conducted by Russia during the Stalinist and German–Russian periods of World War II. In 1812, between 1916 and 1921 as well as 1941 and 1944, Belarus served as the battlefield of the fighting powers, the clashes of which were destroying the country.

The elites of Belarus took part in the Polish national uprisings against Russia in 1768–1772, 1794, 1812, 1831, and 1863–1864. The last of these uprisings – partly of a folk character – has become a legend of modern Belarusian national identity. An important moment of a mental breakthrough, which contributed to the current national awakening in Belarus, was discovering the remains of its lost leaders. Among them was a national hero Konstanty Kalinowski, hanged by the Russians in Vilnius in 1864, secretly buried, found in 2017. He was then solemnly buried in 2019 in the presence of the presidents of Poland and Lithuania and the mass participation of Belarusians.

The West does not know this; they do not teach it in schools. For the average Westerner, Belarus is a “Western Russia,” having for centuries belonged to the Russian state. Lithuanians and Poles look at Belarus differently. It is hard to convey the intricacies of this way of thinking in such a short text, so let it suffice as an explanation to say that, for us, it is like Scotland for the English – except that 200 years ago, a foreign power (also a tyrant) would have detached it from Great Britain and tortured it in various ways. The Belarusian opposition rejected the Lukashenko flag’s post-Soviet symbolism and reached for the old Lithuanian Pahonia (lit. pursuit). The Lithuanians feel what the English would have felt if, after 200 years of foreign rule over Scotland, the Union Jack had appeared, and Scottish citizens, who had been reduced to slavery for generations, had called out: “We want Parliament!” and added: “We were with you at Blenheim and Waterloo, at Balaclava and Omdurman, in Flanders and Somme, at Dunkirk and El Alamein. Here are our banners. Do you still remember them?” Between 1569 and 1863, a sign of the Lithuanian Pahonia was placed next to the Polish Eagle on all the banners of the Republic of Poland and Lithuania, as well as on those carried by the insurgents. Today, it flies over the awakened Belarus. It is not difficult to deduce how Lithuanians and Poles perceive this situation. This is how the English would look at Scotland awakened from captivity. “Were not our hearts burning within us” (Luke 24:32) as now in Poles and Lithuanians? History matters. Without knowing it, it is not easy to understand the current commitment of Poland and Lithuania to the situation in Belarus.

Causes – a systemic crisis

The sources of the crisis of the political system in Belarus are multidimensional. Lukashenko took office in 1994. He has now been in power for 26 years. When reaching for his position, he dealt with a society that grew up under Soviet totalitarian dictatorship – isolated from contacts with the outside world for several decades. Today Belarus has a new active generation, born and raised in an independent Belarus; watching the world either directly, for instance, when traveling to Poland and Lithuania, or on the Internet – by participating in the global circulation of information. The dictator – the former director of a kolkhoz – understood his compatriots a quarter of a century ago and was able to manipulate their mentality. Now, he has trouble understanding the current generation Likewise, his secret services do not understand that – in the era of digitization – covering the faces of police officers with masks, when they are beating the demonstrators, does not prevent them from being identified. This is usually done by comparing photos from social media with the photos of the regime’s advocates, taken by reporters or witnesses. They are no longer anonymous. Their neighbors and families might now see them “in action”[2].

At least since 2011, the economic situation in Belarus has been systematically deteriorating[3]. Russia cannot afford to subsidize this economy with cheap energy resources. In 2016, the US evolved from an importer of crude oil and natural gas to their exporter; Russia came into conflict with OPEC, and all this was compounded by the fuel price crisis caused by the COVID-19 lockdown. The lack of reforms has been weakening the Russian economy for decades. The allied Belarusian economy ceases to provide a standard of living,[4] which guarantees social peace and stability of power[5]. The maneuver to shift responsibility for the current reality onto the predecessors is not feasible after 26 years of dictatorial rule.

Other factors destroying the image of the caring batka (father of the nation) in recent months included: Lukashenko’s grotesquely primitive disregard of the coronavirus health crisis, manifested in his recommendations to drink vodka and not forget about physical activity, the drastic course of the pandemic in the inefficient post-Soviet healthcare system, and the situation where the pandemic severely affected the elderly – his most faithful advocates to date[6].

The insolence of electoral fraud was a profoundly humiliating experience for every rational Belarusian. Perhaps the election results in which the dictator received 50.7% of votes or 53%, would be easier to believe. However, the authorities announced that 80.2% of Belarusians voted for Lukashenko, and only 9.9% for his opponent Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, which was an extreme arrogance[7]. As a nation, the Belarusian people were first humiliated by the apparent lies they were told to believe and then subjected to brutal police terror. Such things simply cannot be forgiven.

Heavily experienced by history, Belarus greatly appreciates peace, understood as the absence of war. The assessment of Lukashenko’s dictatorship from the position of minimalistic expectations of masses of people, the older generation, in particular, could be expressed in this sentence: “Let him rule as he wishes as long as there was no war.” Meanwhile, as a result of the course of action adopted after August 9 to strengthen ties with Russia “within the framework of a Union State,” the Belarusians are increasingly offered the prospect of a country that is entangled in Russian military conflicts – from Syria and Libya to Ukraine. The memory of young Belarusians who were killed in Afghanistan at the command of Moscow has not yet faded. No one would like such a situation to happen again.

There were no significant anti-Russian sentiments in Belarus, which was internationalized and Sovietized to an even greater extent than Russia[8]. Now, people are rising up. Not as fiercely as in neighboring Ukraine, invaded by Russia – after all, there is no war in Belarus. However, it is hard not to notice who stands in the way of the nation’s will and is an ally of the hated dictator. Russia is mentally losing Belarus. The process has not yet taken place. It is in progress, but its direction and perspectives are clear. We, the Poles, remember the mental breakthrough of 1978 (the election of John Paul II) and 1980–1981 (the establishment of “Solidarity” and the introduction of the martial law). Once a nation is awakened, it cannot be easily put to sleep. Repressions can contain the movement – enforce a conspiracy, like “Solidarity” from 1981–1988, but without conducting a genocide similar to the one ordered by Stalin, they will not break it anymore. It will win. It is now a matter of price and time.

Russia in the face of the revolution in Belarus

According to a study carried out by a Russian sociologist Olga Krysztanowska, 58.3% of Russia’s political elite originates from the GRU and the KGB[9]. This fact and the clan-like nature of the system of power in Russia contribute to the three-dimensional structure of overlapping Russian interests in relation to the situation in Belarus. Minimizing costs (including the expenses of confrontation with the West regarding the Belarusian case) and maintaining the sympathy of Belarusian society is in the best interest of Russia understood as a state. As such, this is contrary to the interest of Russia as an empire, which entails the maintenance of Russian control over Belarus while also reducing the costs. Hence the low probability of Moscow’s open military intervention, but, in fact, at any necessary price. Continuing cooperation with Lukashenko, who is widely hated by the Belarusians, is therefore contrary to both the national and imperial interests of Russia. However, the latter is governed primarily by the clan interest of the Kremlin’s siloviks (the KGB members) around Putin. The President of Russia demands that his nation does not see a street rebellion that could overthrow the country’s leader, as witnessed is Belarus. Therefore, Moscow chooses to support Lukashenko, although it is also aware of the price it is paying for this support. He will probably be removed when it exploits the political opportunity created by the current situation – Lukashenko’s full dependence on Russia. However, due to the interest of the Kremlin clan, it must be done in a way and within a timeframe that would not allow making any assumptions that Lukashenko surrendered under the pressure from the “street”[10].

By then, Moscow will have taken over strategic enterprises in Belarus and tighten military control of the country (already so strictly supervised by the Kremlin) although there is no permanent Russian operational force there, only strategically important military installations – the ballistic missile early warning radar station in Hantsavichy and an underwater communications hub of the Russian Navy in Vileyka[11]. Belarus, squeezed in between Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine, is of fundamental military importance for Russia. Although, at first glance, the marshes along the Pripyat River separate its territory from Ukraine, creating an operationally dead area, this is a misleading observation. The possible deployment of large Russian operational groups to the western borders of Belarus would mean crossing this border, potentially providing a basis for effective military blackmail against Kyiv. Moreover, it would weigh on the north-eastern flank of NATO (Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland). So far, however, there have been no significant changes in the military situation in Belarus. The ongoing Russian-Belarusian maneuvers are a military and political demonstration, but they do not fundamentally change the balance of power in the region[12].

Lukashenko’s tactics

Until the outbreak of the protests, Lukashenko created the impression of weaving between Russia and the West. It was all a strategy. He has always been fundamentally connected with Russia. Until 1999, he hoped to become a successor to Yeltsin and pushed for close integration of Belarus and Russia. After Putin took power in the Kremlin, he defended his freedom of decision and power in Belarus. In both cases, he was motivated by personal interest. This also continues today, and this very interest dictates his reliance on Russia – there is no other option. By sending his son to a high school in Moscow in mid-September, he actually gave the Kremlin a hostage and now has no room for maneuver. At the same time, he refuses any dialogue with the opposition[13]. He considers the protests to be an American-Polish-Lithuanian intrigue, sometimes extending the circle of the “guilty parties” to other countries in the region. Thus, provocations evidencing a foreign inspiration for the protests and presenting Lukashenko as a defender of the country against hostile aggression by NATO (Poland and Lithuania) are very likely to happen.

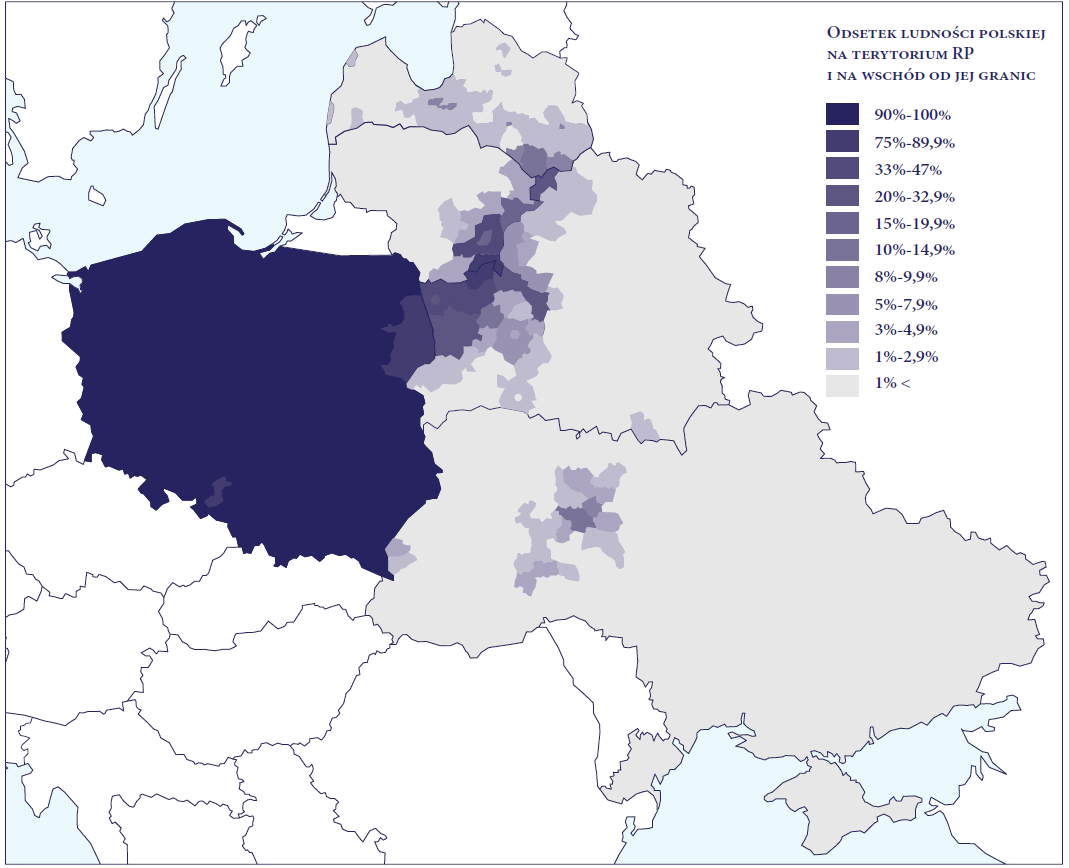

Russia is helping Lukashenko in this propaganda game. Such stories as the shooting down of an American sports balloon on the Polish-Belarusian border in 1995 and the death of two of its pilots – a provocation that was supposed to hinder Poland’s integration with NATO – may be repeated[14]. Lukashenko needs an armed incident at the borders to justify “a state of emergency due to external aggression.” Since 2009, the Russian-Belarusian military maneuvers Zapad include a training scenario in which a Polish uprising in the Grodno region is suppressed (between 400,000 and 800,000 Poles live in Belarus; they constitute about 25% of the population around Grodno and Lida, sometimes being the local majority in the southern part.

Consequently, it is likely that repressions against Poles in Belarus will take place under the slogan of fighting the fifth column. The relations between Poles and the Belarusian national movement are excellent. Historically, there was no hostility between the Poles and the Belarusians. There is no threat that provocations of the authorities in this area will inflame ethnic hatred, but they may turn out to be painful for Poland. Polish citizens would demand an adequate response from the government of the Republic of Poland should any large-scale repression of the regime against Belarusian Poles occurred. Lukashenko and Moscow may, therefore, take advantage of the situation and play this card.

Poland in the face of the situation in Belarus – alliance with the Baltic countries, support in the region, and the reaction of the EU

Poland and the Baltic States – especially Lithuania and, albeit with a delay, Ukraine – reacted the most to the situation in Belarus[15]. Starting from the reunion of the Weimar Triangle (Poland-Germany-France, August 7, 2020) until the decision of the European Council to adopt the Polish Prime Minister’s plan for Belarus, the so-called Morawiecki’s Plan (October 2, 2020), multiple activities took place on the initiative of Poland. They included: the meetings of the Lublin Triangle (Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine), and the Visegrad Group (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary), an online conference of EU foreign ministers and a meeting of this group in the Gymnich format, two meetings of the European Council, the Polish-Lithuanian, Polish-Baltic and Polish-Lithuanian-Romanian inter-presidential declarations, consultations between the President of Poland and the Secretary-General of NATO in addition to talks between the advisors to the Presidents of Poland and the USA[16]. The Polish-funded Belsat TV and Radio “Racja” (Radio Reason), as well as blogger channels such as Nexta created by the Belarusian emigration and operating from Poland, break the information monopoly of Lukashenko and Russia[17].

Morawiecki’s Plan for Belarus, unanimously adopted by the 27 EU countries, is the topmost achievement of this group of activities. It is currently of primarily political importance in two aspects[18]. First, it demonstrates Poland’s ability to push through its projects in the EU and is a signal from the EU as well as Poland and Lithuania to the Belarusians that they are not alone and can count on serious support from the West after overthrowing the dictator. Neither the project of infrastructure investments with the use of EU financial institutions nor the consent for liberalization of the EU visa system for Belarusian citizens can be implemented unilaterally by the EU. They require the cooperation of the Belarusian state, and – as long as it is governed by Lukashenko – it will not agree to such collaboration. Therefore, it is an instrument prepared for a political situation that will come after overturning the dictatorship in Belarus, and not a solution that can be applied today. The EU sanctioned only 40 representatives of the regime, but not Lukashenko. Certainly, this symbolic act will not affect the Minsk’s agenda. Since 1997, the EU has administered various similar punishments on the regime, yet they have never had the expected outcome. Russia has not been penalized in any way. This is a mistake and, as a result, it is encouraging the Kremlin to intensify its interference[19].

The reason for this is the position of the major EU powers – Germany and France. Supporting or opposing sanctions by other countries is of secondary importance.

Germany – growing reputational costs of cooperating with Russia

Germany, linked with Russia by a shared network of interests, the most important manifestation of which is Nord Stream 2, has acted in solidarity with this country already during the Belarusian crisis (Heiko Maas’s visit to Moscow on August 11 and his joint conference with Lavrov, at which they both criticized the US for sanctions introduced on the gas pipeline project)[20]. However, further defense of Putin’s Russia became quite costly for Germany’s reputation after the recent attempted murder by poison of Alexei Navalny. For this reason, Germany had to openly condemn Russia and the Belarusian regime supported by Moscow. However, Maas’s visit to the Kremlin was undoubtedly seen as a sign that Berlin’s real political agenda will aim to pursue common German-Russian interests. Freeing Belarus from Russian influence would probably strengthen Poland and the eastern flank of NATO in general, consolidating it on the basis of fears of Russian revisionism and confirming its pro-American orientation. Given the state of German-US relations, this would mean further emancipation of the eastern flank of the EU from Berlin’s influence. It is doubtful that this would be the wish of the latter.

France – Russia as a counterweight to US domination

Paris, with its traditional anti-American attitude, is looking for a counterbalance to US influence in Russia. France recognizes Belarus as a Russian sphere of influence, as confirmed by President Macron’s visit to Lithuania (September 28, 2020), which involved his verbal condemnation of Lukashenko, but also an appeal to cooperate with Russia in the name of “peace in Europe”[21]. The pursuit of collaboration with Russia is customary for French policy and there is no reason why it should change[22].

The United States – suspension until the election

The revolution in Belarus has started when the USA was at the end of the presidential election campaign. Until the election, Trump will not take any steps that might cost him support. Unless Russia strikes US interests in a way requiring a direct response from Washington – for which Belarus could be used instrumentally – the US reaction in the coming months will remain verbal and symbolic. On September 29, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom acting in concert considered the election in Belarus to be rigged[23]. On the same day, sanctions against the regime in Minsk were imposed by Canada and the United Kingdom[24]. The US refrained from taking this step in anticipation of the European Union’s common position. It did so immediately after EU’s decision – on October 2, introducing restrictions on eight senior officials of the regime[25]. However, the small number of people subject to British, Canadian, and US sanctions, just as in the case of EU, leads to a conclusion that their importance is purely symbolic.

Conclusions

The revolution in Belarus is a complex process and the first great national deed of the Belarusian people since 1918. In fact, given its scale, the first one since the 16th century. It is, therefore, a nation-building process in the mentality of the citizens, an oeuvre of the new generation that grew up in Belarus after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

What is happening in Belarus is irreversible and will eventually win, resulting in the democratization of this country and its reorientation towards the West. The moment when this happens, however, will not be due to the efforts of the Belarusian people themselves, but to the collapse of the Russian control over the situation in their country, resulting from the general condition of Moscow. Consequently, the success of Belarus will have to wait for an appropriate international window of opportunity. However, the mental changes taking place among the Belarusians right now, unlike in 1991, will allow them to take advantage of this situation to build a truly democratic and independent state – naturally having to deal with all of its problems. The process of democratization will be long, and its main obstacle is going to be Russia. Moscow will strive to maintain full control over Belarus at the lowest possible cost, which presages removing Lukashenko from power in the medium-term (in a non-revolutionary manner). The nature of relations with Moscow determines the standpoints of its neighbors – the closest and the other ones, including the major EU powers and the United States. The countries of the eastern flank of NATO as well as Ukraine, which face the Russian threat, already support the Belarusian movement and will continue to do so. In the case of Germany and France, the “Russia first” principle will be dominant in their political agendas. The actions of the EU will remain symbolic, with no significant influence on the course of events in Belarus. As regards the United States, Washington’s approach will be defined after the US presidential election.

[1] Sahanowicz H., Historia Białorusi do końca XVIII wieku, Lublin, 2002, pp. 272–284.

[2] Hakerzy walczą z reżimem: co białoruscy “cyberpartyzanci” mogą osiągnąć w konfrontacji z Łukaszenką?, Biuletyn Informacyjny Studium Europy Wschodniej UW, September 17, 2020, https://studium.uw.edu.pl/hakerzy-walcza-z-rezimem-co-bialoruscy-cyberpartyzanci-moga-osiagnac-w-konfrontacji-z-lukaszenka/.

[3] Kłysiński K., On the verge of crisis? Mounting economic problems in Belarus, OSW Commentary 51, April 6, 2011, pp. 1–6.

[4] Kłysiński K., Belarus: a wave of social discontent before presidential elections, OSW Analyses, June 1, 2020, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2020-06-01/belarus-a-wave-social-discontent-presidential-elections.

[5] Kłysiński K., Lukashenko’s difficult choices, OSW Analyses, July 29, 2020, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2020-07-29/Lukashenkos-difficult-choices.

[6] Olchowski J., Białoruś wobec COVID-19 – bezradność i bezczynność, Komentarze IEŚ, 180 (83/2020), April 30, 2020, pp. 1–3; Kłysiński K., Białoruś wobec pandemii koronawirusa: zaprzeczanie faktom, Analizy OSW, March 18, 2020, https://www.osw.waw.pl/pl/publikacje/analizy/2020-03-18/bialorus-wobec-pandemii-koronawirusa-zaprzeczanie-faktom; Kłysiński K., Żochowski P., Zaklinanie rzeczywistości: Białoruś w obliczu pandemii COVID-19, Komentarze OSW 324, April 3, 2020, pp. 1–5.

[7] Kłysiński K., Mass protests in Belarus, OSW Analyses, August 10, 2020, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2020-08-10/mass-protests-belarus

[8] Marples D. R., Belarus: a denationalized nation, Amsterdam, 1999, p. 140.

Menkiszak M., Gdy Europa choruje, Rosja nie jest lekarstwem, Sprawy Międzynarodowe, 72 (4/2019), pp. 41–57.

[9] Miecik I. T., Czujne oczy czekisty, Polityka, 38 (2470), September 18, 2004, p. 6; Kacewicz M., Czekiści kontratakują, Newsweek, 4 (2003), January 26, 2003, pp. 40–41.

[10] Kamińska A.M., Carte blanche dla Kremla? Ekspert: Putin pozwolił Łukaszence grać rosyjską kartą wojskową – pytanie, za jaką cenę, Polskie Radio 24.pl, September 24, 2020, https://www.polskieradio24.pl/5/1223/Artykul/2588658,Carte-blanche-dla-Kremla-Ekspert-Putin-pozwolil-Lukaszence-grac-rosyjska-karta-wojskowa-pytanie-za-jaka-cene

[11] Rogoża J., Chawryło K., Żochowski P., A friend in need. Russia on the protests in Belarus, OSW Commentary 349, August 20, 2020, pp. 2–3.

[12] Wilk A. (OSW expert) in an interview for Kamińska A.M., Carte blanche dla Kremla? Ekspert: Putin pozwolił Łukaszence grać rosyjską kartą wojskową – pytanie, za jaką cenę, Polskie Radio 24.pl, September 24, 2020, https://www.polskieradio24.pl/5/1223/Artykul/2588658,Carte-blanche-dla-Kremla-Ekspert-Putin-pozwolil-Lukaszence-grac-rosyjska-karta-wojskowa-pytanie-za-jaka-cene.

[13] Zygiel A., Łukaszenka wywiózł syna do Moskwy. Kola będzie się uczył pod zmienionym nazwiskiem, RMF24, September 17, 2020, https://www.rmf24.pl/raporty/raport-bialorus-po-wyborach/news-lukaszenka-wywiozl-syna-do-moskwy-kola-bedzie-sie-uczyl-pod-,nId,4737355.

[14] Federation Aeronautique Internationale. Press Release – Belarus Baloon Tragedy, September 15, 1995, http://www.unm.edu/˜mbas/fai.html.

[15] Iwański T., Ukraine: relations with Belarus suspended, OSW Analyses, September 2, 2020, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2020-09-02/ukraine-relations-belarus-suspended.

[16] Żurawski vel Grajewski P., Orzeł obok znaku Pogoni. Białoruś jako wyzwanie dla polskiej polityki zagranicznej, Rzeczy Wspólne, 33(2), 2020.

[17] Nexta wyrosła na główne źródło informacji o Białorusi, Rzeczpospolita, September 1, 2020, https://www.rp.pl/Media-i-internet/308319886-Nexta-wyrosla-na-glowne-zrodlo-informacji-o-Bialorusi.html.

[18] Polish plan for Belarus has become EU policy – Polish PM, PAP, October 2, 2020, https://www.pap.pl/en/news/news%2C728526%2Cpolish-plan-belarus-has-become-eu-policy-polish-pm.html.

[19] Council Conclusions on Belarus, General Affairs Council, Brussels, September 15, 1997, Press: 269, 103-68/97.

[20] LIVE: Lavrov and German FM Maas hold press conference in Moscow, August 11, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGEKnx55hXk – 1h 18 min – 1 h 23 min.; Ivanov A., #Russia – #Germany – A lot in common or still at odds?, Eureporter, August 14, 2020, https://eureporter.co/frontpage/2020/08/14/russia-germany-a-lot-in-common-or-still-at-odds/.

[21] E. Macron w Wilnie: współpraca z Rosją jest konieczna dla trwałego pokoju, TVP Wilno, September 29, 2020, https://wilno.tvp.pl/50089299/emacron-w-wilnie-wspolpraca-z-rosja-jest-konieczna-dla-trwalego-pokoju.

[22] Menkiszak M., Gdy Europa choruje, Rosja nie jest lekarstwem, Sprawy Międzynarodowe, 72 (4/2019), pp. 41–57; Żurawski vel Grajewski P.,Śmierć mózgowa” Francji?, Klub Jagielloński, December 30, 2019, https://klubjagiellonski.pl/2019/12/30/smierc-mozgowa-francji/.

[23] Mohammed A., Spetalnick M., Emmott R., Exclusive: US, UK, Canada plan sanctions on Belarusians, perhaps Friday, Reuters, September 24, 2020, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-belarus-election-sanctions-exclusive/exclusive-u-s-uk-canada-plan-sanctions-on-belarusians-perhaps-friday-idUKKCN26F2A4.

[24] Smith J., Ljunggren D., Britain and Canada impose sanctions on Belarus leader Lukashenko, Reuters, September 29, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-election-sanctions/britain-and-canada-impose-sanctions-on-belarus-leader-lukashenko-idUSKBN26K2R1.

[25] US Held Back on Belarus Sanctions, Hoping for Joint Move With EU, VOA, September 30, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/europe/us-held-back-belarus-sanctions-hoping-joint-move-eu.; Washington hits Belarus with sanctions as Minsk retaliates against EU measures, Reuters, October 2, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-belarus-election/washington-hits-belarus-with-sanctions-as-minsk-retaliates-against-eu-measures-idUKKBN26N33N.